DİLA KELEŞ

FROM MODERNISM TO POSTMODERNISM IN ART

|

One: Hello!

With the first sketchy writing… ‘‘Sketchy’’ is a choice I make on purpose, meaning that writings I share here will never claim being more than sketchy reflections on contemporary art and artists, based on unsystematic research and prior intellectual make-up of mine. So, feel free to argue, polemicize, respond in any way you find it may serve to reciprocal enrichment in thinking and knowledge. Or, just enjoy!

Two: Messy Words and What Modern Artists Endeavored

There is a mess around expressions like ‘‘contemporary art,’’ ‘‘modern art,’’ ‘‘postmodern art,’’ and ‘‘21st century art.’’ Artists, especially those I met in person, themselves seem to be confused about the conceptual and aesthetic premises of the artistic practice they engage in. In this way occurred my curiosity about how we might deal with these meaning-dictating expressions. I present the outcomes of the research I’ve done on these terms.

To begin with, the major break point we can capture is the one between modern art and postmodern art. (Don’t be hasty for objections about postmodernism, I leave some insufficient space for the controversies the term shelters.) Even if there is no universally agreed checklist to distinguish modern from postmodern art, we can discern the effects of the worldwide socio-political and technological changes on the ways art is understood, practiced, and presented to the viewer.

Very quickly: The time period from the Enlightenment to the apocalyptic second decade of the 20th century can said to be the phase of modern art. Modern artists, mostly men, were acknowledged as geniuses having had godly features to create in the service of the –Western- civilization. Art was a practice no longer in the footsteps of the Catholic Church as it had been for centuries until Renaissance, but of the ideals of individual freedom and progress –scientific, technological and civilizational. So much as questionable the premises of the French Revolution, modern artists were producing high art for an educated public whose taste to appreciate art was developed, in the first hand, by means of economic and symbolic capital. Yet, I recognize that they were talented guys in imitating reality via craftsmen-like skills as did Realists and Impressionists.

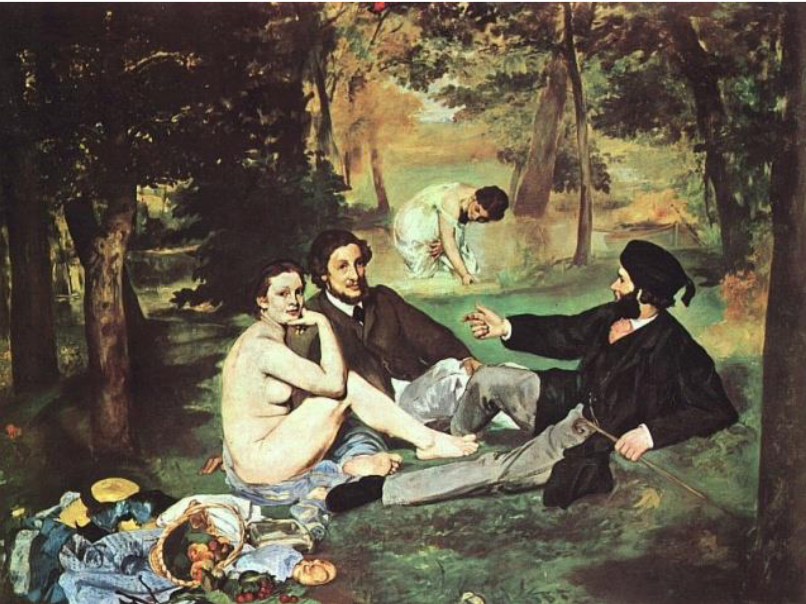

The Luncheon on the Grass from realist Manet is a nice example of modern painting for a couple of reasons. First that attracts the eye is its subject: kind of a Dolce Vita in the country as if poverty and social inequality in France had not been boiling the masses at a time of turbulence that ended up with the Paris Commune in 1871, following the war with Prussia. Second, figures look directly at the viewer’s eye without communicating an important message. The nudity of the woman doesn’t stand for the fertility of the nature or innocence of birth as its previous usages but, instead, nudity for itself is what we are called for to look at. By this painting, Manet influenced many of his Realist contemporaries and Impressionist followers, such as Cézanne and Monet.

The Luncheon on the Grass, Édouard Manet, 1863

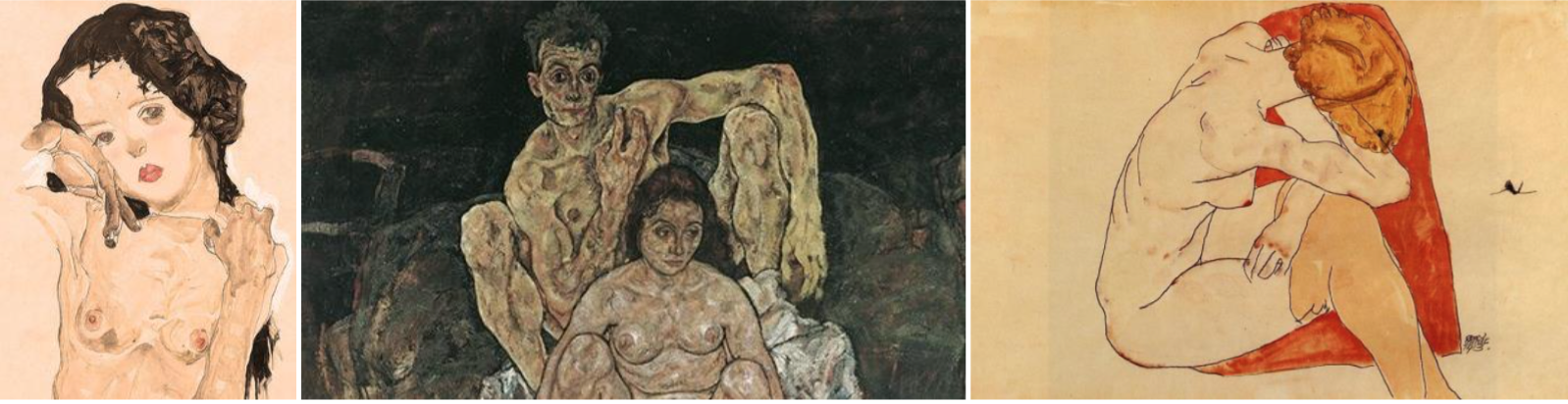

Not only the invention of camera and photography in the late 1800s annulled the sense of being impressed in the viewer by real-like images by modernist painters and sculptors, but crudeness and cruelty of the world scene in around the First World War deeply altered the art space. No longer romanticism with advancement towards the better! Egon Schiele, Expressionist, is my favorite in depicting the agony of modernity through figures who look weak, fragile, disappointed and dispossessed.

Details from larger works, respectively: Black-Haired Nude Girl, Standing, 1910; The Family, 1918; Seated Woman, 1913.

The attention given to the psychological state of the modern individual, encapsulated by a chaotic world where everything like religious belief, social values, family structure, sense of safety and serenity were losing solidity in the face of change, grew in the art space throughout the 1910s and 1920s. It was in such a context that Dadaists, Cubists and Surrealists interested in and produced works on the human subconscious. Dreams, anxieties, fantasies and psychological drives were represented by uncompromising imagery.

Three: Postmodernism and Art

And the debate about postmodernism begins with the timeline that marks on the aftermath of the Second World War. Humanity was in shock with the Holocaust, Atomic Bombs, then after the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Vietnam War and the human flesh expenditure of capitalism. The avant-garde narrative, leaning on the idea that all progress is good, was overturned by postmodern artists.

Guernica, Pablo Picasso, 1937

I guess that are few people, among those who have a minimum of interest in art, who don’t know Picasso’s famous response to the German military officer asking him if he was the one who painted Guernica, the huge size (349 cm x 775 cm) mural depicting the chaos, human suffering and environmental devastation resulted from the German bombardment of the village: ‘‘No, you did.’’

Art was passing through a new phase of evolution. Postmodern artists rejected the modernist emphasis on the individual as the universal subject of rights, and this was no surprise for a changing status of art vis-à-vis the social. The strong pressure of identity movements in the U.S. and elsewhere by the oppressed ripped off the mask of abstract liberalism. To an accumulated repertoire of painful testimony to world wars and disclosure of suffering by women and colored people, 1950s’ propagation of consumerism sharpened the keen edge of artistic engagement.

The rise and flourishing of Pop Art should be understood, I would argue, as an agonistic response to this tragedy-like sum of collective experience. Although the number of commentators to Pop Art who see it as a product of the consumerist culture is not negligible, I notice in the works of Andy Warhol or Jasper Johns a genuine mockery of post-industrialism. I sense in Pop Art usage of daily industrial tools, advertisement materials and iconography of mass consumption kind of a critique of the sociality we go along with without questioning. The artists seem to be calling back our concern for morality and death when consuming symbols.

Gun, Andy Warhol, 1981-1982

In the subsequent decades, artists kept their posture that did not remain unresponsive to the socio-political dynamism that encircled the art space. Instead of a psychological approach to human experience, the social context began to be taken into account. With the impact of Deconstructivism in the 1980s, the message of the works of art overwhelmed the works themselves. Departing from the idea that all meaning is unstable and bounded by the viewer’s personal history, there emerged new artistic media that cherished viewer’s active participation. Video Art, Performance Art and Installation Art can be listed as those branches where the receiver is invited to interrogate her/his values and regard that is always-already shaped by the structures of power. Image production has become more a vehicle of shaking the viewer than granting a sense of serenity.

If we are to re-evaluate the criticisms that target postmodernism for its over-relativizing processing of universal truths, and for sure this needs re-evaluation even after a bunch of relevant literature, we still cannot make so without the lessons it has given to problematize our ‘‘ways of seeing.’’ In the last part of this sketch, I give some concrete examples to how this now-discredited adjective ‘‘postmodernist’’ nourished the way art has become an organic being in itself in showing us an exit way towards we, real persons, experience the world and act upon it.

Four: Recent Examples to Postmodern Art and Concluding Remarks

Banksy, whose official identity is not revealed (and God knows what would his fate be otherwise), is an English-based artist and political activist mostly known for his graffiti work against the surface romanticism of freedom in a capitalist earth. He is harshly critical of the American Dream of meritocracy and individual liberty, as much as he is of police violence and authoritarianism that target urban anti-government movements.

Mona Lisa Rocketlauncher, Banksy, 2007-2008

By this graffiti work, Banksy reminds us the totalitarian character of the Western so-called civilization. Mona Lisa is represented with a rocket on her arm, implying the cultural hegemony of the West over underdeveloped countries. The figure stands for the ideological intoxication of the Third World subject while its sources are being appropriated with any means, arms being no exception!

David Černý is a Czech fellow, scandalous for his critique of the European Union and its un-amazing commitment to peace, equality and rule-of-law.

Entropa, David Černý, 2009

This symbolism-loaded installation by Černý is exhibited in the EU Council headquarters in Brussels in 2009 when Czech Republic came to the EU Presidency of the term. Its name, Entropa, is a word game Černý played with Evropa (meaning Europe in Czech) and Entropy (meaning disorder). The representation of countries is more than funny. Germany is made of swastika-shaped network of highways, France is shown on ‘‘STRIKE,’’ the Netherlands is sunk under water on whose surface only minarets remain visible, Cyprus is split into two and Bulgaria is symbolized with Turkish squat toilet. One needs not to be very imaginative to decipher the messages about the socio-political problems inside the Union; such as, Nazi past of Germany, leftist pressures on the government in France, social exclusion of Muslim immigrants in the Netherlands, Turkish-Greek political conflict in the Cyprus island, and positioning of Bulgaria as the toilet of the EU. Funniest is the $500.000 USD grant Černý received from the Czech government which thought it would commission a group of Czech artists for a collectively created work of art to celebrate the country’s ascension to the EU Presidency!

Last one from Gezi.

Anonymous (to the best of my knowledge), 2013

This graffiti image is a well-known one for whosoever witnessed or participated to Gezi Protests in Turkey. It is not only critical of the media censorship of the countrywide street movements, but also an example in case to the postmodern art some features of which I discuss in this writing: abolishing the frontiers between high art and popular art; promoting viewer’s interaction with the work; getting inspired by the socio-political dynamism around; and, conforming its status of being a strong tool to satirize macro politics.

Let me put my concluding remarks to the point I entered into the debate around contemporary art. Clearly, any one of us would check, if feels necessary, what contemporary means; pretty clear in giving us the result that ‘‘that which is going on in actual time.’’ More I tried to deal with the tendency the artists exhibited in the timeline by what they performed in the name of art. And it seems that art did not and cannot stand in a sterile existence from what’s going on around. Whatever conclusions critical thinking drives us to draw, postmodern art should certainly be –applauded or detested- understood as an altered practice in the historical trajectory of art which is no longer confined to enclosed communities in the service of this or that, but one in the search of emancipation. Individual, collective…

------------------------

(1) My re-reading does not challenge the Western canon, but is constructed upon available sources that don’t question its canonic status. Please feel synchronized with me in the uneasiness such an approach causes.

(2) Not shocking that artists such as Picasso, Matisse, Kandinsky and Duchamp are considered to be Modernist by some, and Postmodernist by others. I wish you are patient enough to scan the whole text to reason according to what criteria I distinguish modernists from postmodernists.

|